We typically spend 80% of our time indoors, where the quality of the air we breathe depends on the age and type of building we occupy, as well as indoor pollution and outdoor pollution sources. But also playing an important role is the kind of HVAC system used to heat, ventilate and cool the building, according to new research from the University of Utah.

Using the Salt Lake City campus as a living laboratory, the College of Engineering teamed up with Facilities Management and occupational and environmental health researchers to explore whether and how outdoor air pollution affects indoor air quality. They found that indoor air quality on campus was generally good. However, depending on a building’s HVAC system, fine particulate pollution, or PM2.5, from wildfire smoke can infiltrate buildings, while pollution associated with dust events and winter inversions is kept out.

The study found the issue lies with commercial HVAC systems that use air-side economizers. Using special duct and damper arrangements, this technology reduces energy use by drawing air from outdoors when temperature and humidity levels are optimal, such as cool summer and fall mornings. This helps with energy efficiency, but if the air is smoky that day, the system could pull in particulate pollution and some particles make it past the filters, according to chemical engineering professor Kerry Kelly, who is overseeing the research.

Campus as laboratory

“Our buildings are big and they’re complicated, and oftentimes they’ve been added onto and integrated with different kinds of systems,” Kelly said. “So I think the management is challenging, but the good thing is it is a very solvable problem. Even simple solutions like portable air filters do a great job.”

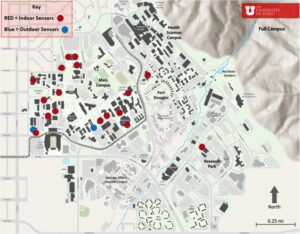

The ongoing project deployed low-cost wirelessly connected sensors in 17 indoor and two outdoor locations in an effort to characterize what happens with indoor air quality when particulate pollution is elevated during dust storms, winter inversions and wildfire season—which present different kinds of PM2.5 and occur at different times of the year.

“We look at the ratio of the indoor particulate matter measurements to that of the outdoor particulate matter measurements. The closer that value gets to one, which means more of the particulate matter is going to be sourced from outdoors versus indoor sources,” said study leader Tristalee Mangin, a graduate student in chemical engineering. “We looked at those ratios and then did analyses based on the different groupings of HVAC types.”

Continue reading Brian Maffly’s “Does outdoor air pollution affect indoor air quality? It could depend on buildings’ HVAC” on @theU.