Pain is a necessary biological signal, but a variety of conditions can cause those signals to go awry. For people with chronic pain, the root is often faulty signals emerging deep within the brain, giving false alarms about a wound that has since healed, a limb that has since been amputated, or other intricate, hard-to-explain scenarios.

Patients with this kind of life-altering pain are constantly looking for new treatment options; now, a new device from the University of Utah may represent a practical long-sought solution.

Researchers at the University of Utah’s John and Marcia Price College of Engineering and Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine have published promising findings about an experimental therapy that has given many participants relief after a single treatment session.

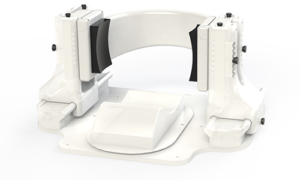

At the core of this research is Diadem, a new biomedical device that uses ultrasound to noninvasively stimulate deep brain regions, potentially disrupting the faulty signals that lead to chronic pain.

The findings in a recent clinical trial, published in the journal Pain. This study constitutes a translation of two previous studies, published in Nature Communications Engineering and IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, which describe the unique features and characteristics of the device.

The study was conducted by Jan Kubanek, professor in Price’s Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME), and Thomas Riis, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab. They collaborated with Akiko Okifuji, Professor of Anesthesiology in the School of Medicine, as well as Daniel Feldman, graduate student in the Departments of Biomedical Engineering and Psychiatry, and laboratory technician Adam Losser.

The randomized sham-controlled study recruited 20 participants with chronic pain, who each experienced two 40-minute sessions with Diadem, receiving either real or sham ultrasound stimulation. Patients described their pain a day and a week after their sessions, with sixty percent of the experimental group receiving real treatment reporting a clinical meaningful reduction in symptoms at both points.

“We were not expecting such strong and immediate effects from only one treatment,” says Riis.

“The rapid onset of the pain symptom improvements as well as their sustained nature are intriguing, and open doors for applying these noninvasive treatments to the many patients who are resistant to current treatments,” Kubanek says.

Diadem’s approach is based on neuromodulation, a therapeutic technique that seeks to directly regulate the activity of certain brain circuits. Other neuromodulation approaches are based on electric currents and magnetic fields, but those methods cannot selectively reach the brain structure investigated in the researchers’ recent trial: the anterior cingulate cortex.

After an initial functional MRI scan to map the target region, the researchers adjust Diadem’s ultrasound emitters to correct for the way the waves deflect off of the skull and other brain structures. This procedure was published in Nature Communications Engineering.

The team is now preparing for a Phase 3 clinical, trial which is the final step before FDA approval to use Diadem as a treatment for the general public.