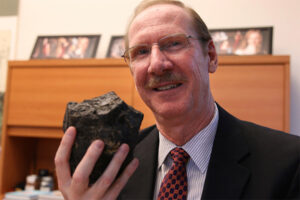

University of Utah chemical engineering professor Eric Eddings has received a $1.9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for continued research on converting coal pitch into carbon fiber, a process that could help revitalize the coal industry by converting coal pitch into useful materials for products such as cars, prosthetics, recreational equipment and other light-weight items.

University of Utah chemical engineering professor Eric Eddings has received a $1.9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for continued research on converting coal pitch into carbon fiber, a process that could help revitalize the coal industry by converting coal pitch into useful materials for products such as cars, prosthetics, recreational equipment and other light-weight items.

The grant will allow researchers to scale up and verify lab-scale developments on the production of isotropic and mesophase coal-tar pitch for carbon fiber production. This new phase will use coals from five coal-producing regions in Utah, Wyoming, West Virginia, Alaska and Illinois.

Researchers will also investigate the production of a silicon carbide by-product from residual coal char and develop an extensive database and suite of tools for data analysis and economic modeling related to the coal-to-carbon-fiber process. This will also help them assess the economic viability of coals from different regions for producing specific products.

Also involved in the project are University of Utah School of Computing’s Distinguished Professor Christopher Johnson and professors Valerio Pascucci and Mike Kirby. All three are members of the U’s Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute. Additional project team members include professor Maohong Fan from the University of Wyoming and professor Anthony Szwilski from Marshall University.

Typically, when coal is heated it produces hydrocarbon materials that are burned as fuel in the presence of oxygen. But if it is heated in the absence of oxygen — as in the cooking process smelters use to produce iron — those hydrocarbons can be captured, modified and turned into an asphalt-like material known as pitch.

The pitch can then be spun into carbon fibers used to produce a composite material that is strong and light. Most carbon-fiber composite material is made from a derivative of petroleum known as polyacrylonitrile, but that process is expensive.

This new process can also be better for the environment than just burning coal for fuel because processing coal for carbon fiber produces “substantially” less carbon dioxide, Eddings said.

Finding a new use for coal other than for energy could be a boon for those communities that have been hurt by the slowdown of the industry.

“There’s an abundance of coal, and we would like to find an alternative use for it. It is a huge natural resource in the U.S., and we have a whole coal-mining community that is desperate for a new direction,” said Eddings when he first announced the research in 2016. “If we can find an economical way to use coal to produce carbon fibers and have enough useful products so there can be a market for it, then they have that new direction.”

Eddings’ grant is one of three new projects funded by the DOE to find ways to turn coal into much-needed materials.